By Sarah Rodehorst

HR professionals are familiar with the WARN Act, known formally as the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act which went into effect in 1989. It’s an easy one to remember since it requires employers to provide written advance notice in situations of qualified plant closings and other mass layoffs. Created to protect employees, their families, and communities by requiring that employers provide sixty calendar days advance notification, the lead time allows everyone involved to prepare for the transition and brace for potential impact.

The WARN Act is a federal act that targets employers with 100 or more employees. Failure to adhere to the WARN Act is costly; employers that violate it are liable for an amount equal to back pay and benefits for the period of the violation (up to 60 days) for every affected employee. Not to mention the possibility of individual or class action lawsuits.

Repeat after me: As an employer, it is your responsibility to understand your organization’s obligations. Being WARN Act-savvy might feel like enough to ensure compliance when layoffs are imminent. Nothing could be further from the truth. Not only have workforces and workforce reductions become increasingly complex (especially with remote and hybrid work arrangements), but state WARN laws have also come into effect. Many of them have even stricter requirements than the federal WARN Act and differ in terms of thresholds and definitions. And while compliance with the state WARN statutes was considered voluntary, mandatory requirements and enforcement mechanisms are being added.

Here are some insights into select state mini-WARN Acts:

Georgia

Georgia adheres to the provisions created by the federal WARN Act. There are specific WARN Act triggers for Georgia employers:

- Closes a facility or discontinues an operating unit permanently or temporarily, affecting at least 50 employees, not counting part-time workers, at a single employment site. A plant closing also occurs when an employer closes an operating unit that has fewer than 50 workers, but that closing also involves the layoff of enough other workers to make the total number of layoffs 50 or more;

- Lays off 500 or more workers (not counting part-time workers) at a single site of employment during a 30-day period; or lays off 50-499 workers (not counting part-time workers), and these layoffs constitute 33% of the employer’s total active workforce (not counting part-time workers) at the single site of employment;

- Announces a temporary layoff of less than six months that meets either of the two criteria above and then decides to extend the layoff for more than 6 months. If the extension occurs for reasons that were not reasonably foreseeable at the time the layoff was originally announced, notice need only be given when the need for the extension becomes known. Any other case is treated as if notice was required for the original layoff; or

- Reduces the hours of work for 50 or more workers by 50% or more for each month in any six-month period. Thus, a plant closing or mass layoff need not be permanent to trigger WARN.

Maine

Maine follows the parameters of the federal WARN Act with one significant difference. Maine requires a 90-day notice of a covered establishment, which is closing or relocating. “Covered establishment” means any industrial or commercial facility or part thereof that employs or has employed at any time in the preceding 12-month period 100 or more persons.

The Maine mini-WARN states that any employer who closes or engages in a mass layoff at a covered establishment is liable to eligible employees of the covered establishment for severance pay at the rate of one week’s pay for each year, and partial pay for any partial year, from the last full month of employment by the employee in that establishment. The severance pay to eligible employees is in addition to any final wage payment to the employee and must be paid within one regular pay period after the employee’s last full day of work, notwithstanding any other provisions of law.

New Jersey

Effective April 10, 2023, recently signed legislation amends New Jersey’s NJWARN. Amended NJWARN includes a new provision that provides, “For purposes of this section [the section requiring notice and severance pay], “employer” includes any individual, partnership, association, corporation, or any person or group of persons acting directly or indirectly in the interest of an employer in relation to an employee, and includes any person who, directly or indirectly, owns and operates the nominal employer, or owns a corporate subsidiary that, directly or indirectly, owns and operates the nominal employer or makes the decision responsible for the employment action that gives rise to a mass layoff subject to notification.”

This language expands the range of individuals and businesses that can be held liable for the mandatory severance pay, including potential managers involved in the decision to lay off employees, corporate officers, and private equity firms involved in the sale or purchase of a shuttered business.

Like Maine, New Jersey also requires 90-day notice. Amended NJWARN provides that employees who are denied the required 90 days’ notice are entitled to four weeks of severance pay as a penalty, in addition to the greater of (i) one week of severance pay for each year of service, or (ii) any severance pay to which they are otherwise entitled under a collective bargaining agreement or other policy/plan of the employer.

As you can see, the level of detail in the WARN and mini-WARNs is intense. Among the states with mini-WARN acts are California, Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee and Wisconsin. The city of Philadelphia also has its own WARN Act. Staying abreast of the compliance requirements of these Acts is more than a full-time job, not to mention a specialty that might be rarely used by the HR team.

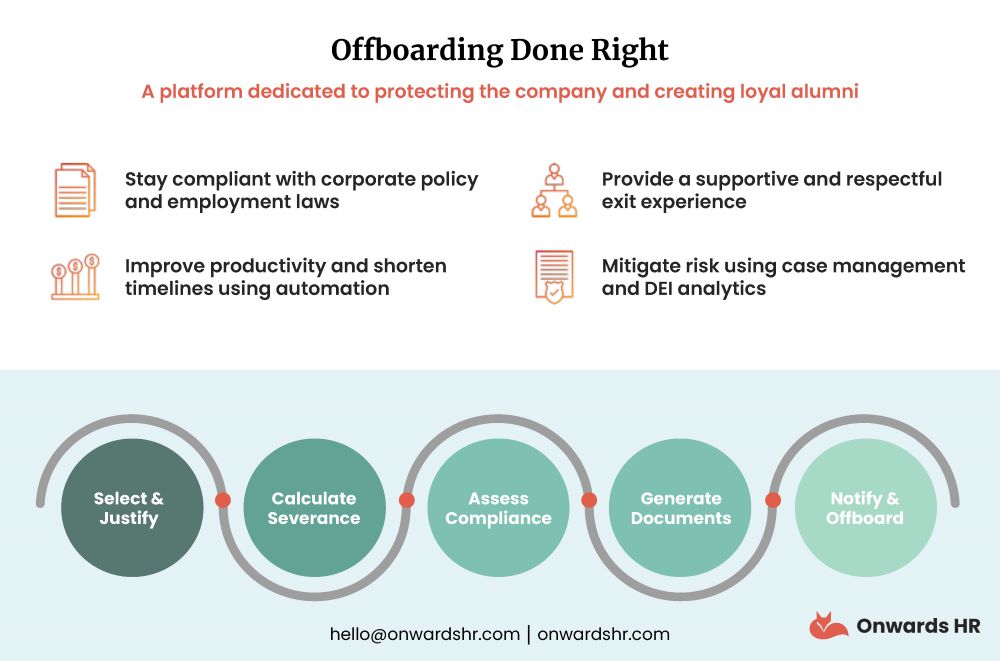

Limiting liability during layoffs requires a knowledge of the federal and state WARN Acts, coupled with the ability to run a disparate impact analysis for all layoffs companywide. It’s the only way to ensure the layoff isn’t having a negative impact on certain workers based on age, race, or gender. Layoffs are stressful, especially for HR professionals, which is why planning ahead, staying current on relevant federal and state laws and partnering with a vendor that specializes in compliant offboarding is necessary.

leadership positions at startup and Fortune 500 companies and now leads Onwards HR as CEO

and co-founder. As a women-in-tech evangelist and diversity, equity, and inclusion champion,

Sarah’s thoughts on layoffs, women in technology, and DEI in the workplace have appeared in

publications including Wall Street Journal, CNN Business, NPR, SHRM, HR Professionals, HR Executive, HR Brew, and Vibe. In 2021, she was a Women in Technology Woman of the Year Finalist in Engineering.