By Nela Richardson

Last month we witnessed a second Trump impeachment in three years. It’s a remarkable time in political history and there’s a lot to unpack.

But this isn’t that type of article. I’ve taken a grand total of one political science class and whatever history was required in high school. In short, my opinion on events is more suited to sharing over a drink in Midtown or in debate with my 13-year-old.

So, while the country’s attention was affixed to politics last week, I dug into the Bureau of Labor Statistics release of the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Here are three reasons why.

#1 Macro conditions, not politics, shape the economy

In the past 100 years we’ve seen only three other impeachment proceedings — against Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton and Donald Trump. Nixon resigned in 1974 knowing his impeachment was imminent. The Senate acquitted Clinton in 1999 and Trump in 2020.

In 1974, the economy was in recession. Inflation was soaring. Unemployment would rise to over 8 percent over the next 12 months. The Federal Reserve, trying to contain inflation, had hiked interest rates, pushing the benchmark federal funds rate to 12 percent in August 1974 as Nixon’s impeachment inquiry began.

The economic environment was quite different in 1999. The unemployment rate was 4.5 percent in 1999 and had fallen to 4 percent by the end of Clinton’s term in 2001. The federal funds rate hovered moderately around 5 percent.

During Trump’s first impeachment in 2019, unemployment was at a 50-year low and stayed there until right before the onslaught of the pandemic in March. Borrowing costs for consumers and businesses also were low, with the federal funds rate around 1.55 percent after the Fed cut rates three times in the second half of 2019.[1]

As of the third quarter of 2020, the economy has recovered about two-thirds of the output lost in the second quarter of the year, when GDP plummeted at a -33 percent annualized rate. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that some 10 million people who had jobs in February don’t now. Weekly jobless claims sounded a warning on Thursday, rising to 965,000 new claims in single week, the highest since August.

For small businesses, those big jobless claims numbers represent personal sacrifice, laid-off colleagues, lost revenue, and uncertainty.

Small business confidence dropped in December for the first time since May according to a closely watched survey from the National Federation of Independent Businesses. Despite rock-bottom interest rates, only 8 percent of business owners think it’s a good time to expand, a troubling finding for those of us hoping that a second round of fiscal stimulus from the Payroll Protection Program will be a salvo.

On the horizon is President-elect Biden’s new $1.9 trillion coronavirus and stimulus plan, which may take time to move through the political process, even under unified government. In the 2021 economy, the pandemic, not politics, is still calling the shots as it constricts our lives, our economic activity, and confidence on Main Street.

#2 Deflation, not inflation, is the bigger short-term risk

Main Street is built on confidence. Think about it. To bankroll ideas, entrepreneurs often tap into their own savings. They take out loans, seek investors, and raise money from friends and family. Hey, maybe you’re that friend. Putting money behind an idea requires a high degree of confidence not only in the entrepreneur themselves, but in the economy.

And Main Street confidence–or the lack of it–trickles up to the macro level. Worried companies and consumers invest and spend less, reducing supply and demand for goods and services.

While some market watchers think high federal debt and low interest rates will eventually trigger an uptick in inflation, the more immediate concern is too little inflation. By limiting demand and the productive capacity, the pandemic has been deflationary as opposed to inflationary.

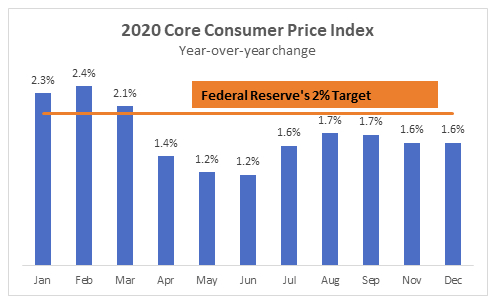

The chart below shows the Consumer Price Index, which measures the cost of goods and services minus volatile food and energy prices. The slowdown in economic activity caused by pandemic lockdowns caused the CPI to fall to 1.2 percent in May and June. It’s now edging back closer to the Fed’s 2 percent target but slid again in November as a second wave of viral infections surged.

#3 Inflation is being remixed by the Federal Reserve

Inflation can be described as a general rise in the overall price level of goods and services, everything from haircuts to healthcare. Main Street’s concern is that rising inflation reduces the purchasing power of a dollar and decreases the value of savings and investments. (Roll that gold and/or bitcoin commercial now).

Starting in 2012, under the direction of Federal Reserve Chair (and baseball enthusiast) Ben Bernanke and his successors, the central bank has stuck to an inflation target of 2 percent. But unlike the inflation bouts of yesteryear, inflation for the past two decades has been mild for a hodgepodge of reasons, including the global supply chain, improvement in monetary policy, and automation.

In this environment, the Fed has discovered that an unemployment rate under 4 percent can be sustained without stoking inflation higher than 2 percent. That means monetary policy can be used more aggressively to stimulate an ailing job market without triggering a rapid increase in prices.

So the Fed has changed its tune on inflation and is encouraging it to go up instead down. The central bank recently remixed its policy in an attempt to push inflation above 2 percent for a significantly long time. This is a new take on the 2012 classic that Fed policymakers call “average inflation targeting”.

Inflation has a lot of moving parts. One of the biggest is the confidence, which convinces people to spend instead of save and drives economic growth on Main Street.

ADP Chief Economist